Why Venture Math is Different for Family Offices

The intrinsic edge of evergreen capital

People often ask (read: I explain unprompted) what distinguishes family office venture capital platforms like Sopris from “conventional” VC funds.

The short version: Family offices and other evergreen vehicles have a few commonly understood advantages in venture strategies. They’re more flexible in how they can pick and structure investments, they focus more on investing than on fundraising/reporting, and they’re better aligned because “eating your own cooking” emphasizes returns, not getting fat on fees.

But the biggest edge is duration, which is often misunderstood. People seem to conflate long-term orientation with infinite patience. While family offices can be more patient with respect to capital deployment, portfolio maturation and exits, that patience has limits. Rather, the real unlock of duration is the ability to compound via re-invested proceeds, which enables an entirely distinct approach to portfolio construction.

This is not to say traditional VC funds are “bad.” As Bill Gurley recently put it: “There are people and firms taking action that change the state of the field and I think they're all acting reasonably and in their best interest. The aggregate effect may not be positive for the world, but I'm not ascribing malintent...”

Ultimately, VC as an asset class is far from one-size-fits-all. The key for entrepreneurs navigating early stage capital markets is clarity. Know what you’re trying to achieve and seek capital that specifically aligns with it.

The Unbearable Lightness of Having No LPs

Shunning outside capital gives family offices several strategic/qualitative advantages in direct venture capital strategies, including flexibility, focus, and incentive alignment.

Flexibility

Family office VCs are not constrained by a fixed mandate or portfolio construction.

In a closed-end fund, LPs need to understand exactly what they are signing up for. This forces GPs to lock in a strategy and structure upfront. Once set, they can’t easily deviate from it.

In contrast, family offices generally don’t need to commit to a specific mandate. This means that they can stretch across asset classes and investment structures. John Zito, Co-President of Apollo, explains the advantage of this flexibility (structured credit in his case, but the logic carries):

The directive is: do the best risk / return.

Most firms are set up by fund, they're set up by okay, go find a company or a preferred or a debt instrument that's going to make 15% rates of return. And we're set up, let's assess the company, let's assess the best solution for that company.

It could be a buyout, it could be an investment grade solution, regular way bond deal. But understand risk, reward, or cost of capital structure per unit of risk. It's a completely different framing because we have no walls.

Source: John Zito on Invest like the Best Podcast

This flexibility means that family office VCs can be better capital partners to entrepreneurs. When the mandate is just “make money,” investors can offer bespoke capital solutions that fit the needs of the company, rather than something off-the-shelf (e.g. VCs who have rigid ownership targets).

Focus

Family office VCs don’t have to fundraise. Instead of churning through 1,000 point questionnaires from prospective LPs, family office investors can dedicate bandwidth to sourcing, execution, and supporting investments. Reporting still exists, but it’s far less onerous.

Every minute not spent on the “annoying stuff” is more time spent helping companies create enterprise value.

Incentive Alignment

Family office investors don’t live off of management fees. The incentives are simple. They only make money if investments do well. That drives tighter alignment with entrepreneurs, while avoiding many of the distortions that come from the pressure of managing outside capital, like:

Pushing companies to take more capital than they need, to put more fee-carrying capital to work

Keeping companies on the fundraising treadmill so they can show paper markups

Performing cap table gymnastics to inflate headline valuations

For many venture capital firms, the product is the next fund. With this backdrop, it’s no wonder that valuation distortions are endemic across the venture ecosystem today. As Bill Gurley put it:

The thing that most people may not believe, but I guarantee you is true — no one has an incentive to get the marks right. For those that don't know this world — private investing, both on the PE side and the VC side — is this weird world where the GPs, the people responsible for the investments, report the price to the LPs. They get to pick it… But the thing people may not realize is, the managers of the VC group at the large endowments have no incentive to try and right-size this number. In fact, many of them are bonused on paper marks. So if anything, they have the reverse incentives to get them right.

Source: Bill Gurley on Invest like the Best Podcast

When you’re “eating your own cooking,” the incentive structure is brutally simple1: make money.

Here for a Good Time AND a Long Time

The most profound advantage of family offices (and other evergreen capital vehicles) comes down to the simple math of duration. But the benefits of long-term orientation are often misunderstood.

The prevailing view is that family offices are just more patient with respect to capital deployment and timing exits.

It’s true that evergreen investors are not forced to invest on a timeline or sell early due to a fund life cycle. Instead, they can wait for favorable market conditions and ride out asset level volatility.

Traditional funds, by contrast, face mounting pressure to return capital on schedule. You can see this playing out in rise of PE continuation vehicles and the growing popularity of PE and VC secondaries (e.g. Yale Endowment’s “Project Gatsby” to offload $2.5bn in PE/VC secondaries).

But the idea that family offices can wait indefinitely for liquidity has limits.

Some family offices benefit from alternate income streams. Take Steve Ballmer, who seems to be clipping (lol) ~$1bn in Microsoft Dividends each year.

You’re just trying to shovel the money that is coming in the door, out the door.

Source: Acquired Podcast Interview with Steve Ballmer

Groups like Ballmer’s would have far less pressure to generate liquidity from their investments2.

But many family offices don’t have that kind of external cash flow. Those groups need to return capital in order to fund new deals.

Many believe that the lack of a “sell by” date means that evergreen investors can exhibit more patience around startup growth, particularly in early years when it takes time for product-market fit to materialize. That is sort of true. Ultimately, all investment outcomes are governed by rates of change. No rational investor, evergreen or otherwise, is going to sit around content with flat growth indefinitely.

Double It and Give It to the Next Person

The real advantage of duration is compounding. This unlocks a different style of portfolio construction, which often aligns better with founders than the standard spray-and-pray VC playbook.

A recent paper from Michael Mauboussin and Dan Callahan at Morgan Stanley lays out the math behind this idea.

An essential point is that mean/variance optimization generally assumes you are deciding based on one period. But the approach is different if you consider multiple time periods and your goal is to maximize the likelihood that you will have the most money at a date far in the future.

This insight came from John Kelly, a physicist who used information theory to develop a strategy for optimal betting over the long term. Kelly noted that if a gambler made one bet of one dollar per week but could not reinvest his winnings, he should maximize expected value. This is Markowitz.

But the math changes if the winnings are reinvested from one period to the next.

Instead of seeking the outcome with the best arithmetic mean, the objective is to find the opportunity with the highest geometric mean. This is called the Kelly criterion, or Kelly strategy.

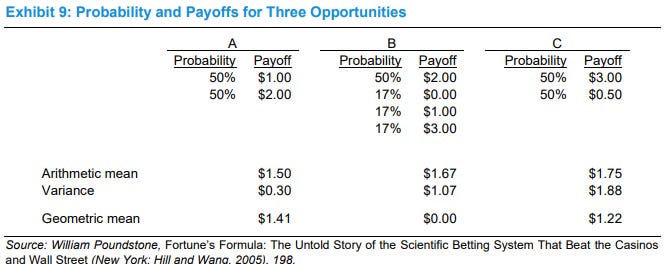

The Kelly criterion can’t be directly applied to venture capital because the probabilities/risks/payouts are not known in advance, but the concept is still instructive:

The probabilities and payoffs allow us to calculate the arithmetic and geometric means. We can see that of the three opportunities, the expected value, or arithmetic mean, is lowest for A, in the middle for B, and the highest for C. If you bet the same amount every time you should maximize expected value. Markowitz would say that the best choice is a function of an individual’s preference. But opportunity C is the most attractive, all else being equal.

If your profits or losses in the prior period are reinvested into your bankroll, you should use the Kelly criterion and maximize the geometric mean. In this case, A is the most attractive opportunity and C is second best…

The main takeaway from this discussion is that there is a crucial difference between selecting the opportunity with the highest expected value for one period and reinvesting returns in opportunities over multiple periods. Mean/variance optimization is built for the former and geometric mean maximization works for the latter.

Source: Morgan Stanley

Closed-end funds don’t get to reinvest proceeds. They are playing a one-shot game. Thus, it is rational for them to optimize around expected value per fund. This is why the spray-and-pray approach of having 1-2 massive wins in a fund is so common.

But this reliance on power law outcomes becomes a trap. Everything gets underwritten to be a potential billion dollar exit, whether it deserves to be or not. “Perfect” is prioritized while sacrificing a multitude of “good” to “great” outcomes.

Family office investors can play a different game because they can roll proceeds into future investments. Modest outcomes still matter because they become fuel for the next investment.

This is not to say that family office VC investors aren’t looking for big outcomes. But they can use a more measured approach to achieving them. The power law is ultimately a statistical phenomenon, not a set of operating instructions. The traditional Silicon Valley obsession of chasing home-run outcomes crowds out meaningful, durable wins that could be life-changing outcomes for entrepreneurs.

That said, there are real constraints for family office VCs too. The biggest challenge is scale. Big firms with billions in AUM have the infrastructure to power robust sourcing, whether via content or brute-force. This can be critical since those strategies are incumbent on intercepting the rare category-defining company.

Ultimately, I think raising capital really is a choose-your-own-adventure for founders. If you want to shoot for a bazillion dollar outcome with haste, you should raise from a traditional VC. If you want a more measured approach, seek alternative capital. The ongoing maturation of the VC industry means that it’s not a one-size-fits-all product.

Disclaimer:

This content is being made available for educational purposes only and should not be used for any other purpose. The information contained herein does not constitute and should not be construed as investment advice, an offering of advisory services, or an offer to sell or solicitation to buy any securities or related financial instruments in any jurisdiction. Certain information contained herein concerning economic trends and performance is based on or derived from information provided by independent third-party sources. The author believes that the sources from which such information has been obtained are reliable; however, the author cannot guarantee the accuracy of such information and has not independently verified the accuracy or completeness of such information or the assumptions on which such information is based.

Most PE and VC firms do have some level of required GP commitment alongside the LPs, but it averages around 3-5%. Not comparable to an effective ~100% GP commitment IMO.

I’m sort of using Ballmer’s philanthropy as an analogue for investment activities, because it sounds like he has pretty limited investment activities outside of the Clippers, Microsoft and Index Funds. I couldn’t think of anyone else off the top of my head who is printing dividends like that.