Macro Headwinds Cloud the Outlook for Healthtech Venture Capital

Worth less, but not worthless

There seem to be two emerging views on where the venture capital asset class is heading.

On one hand, there’s a view that the worst is over - that we are “mostly through this downturn” as Union Square Ventures’ Fred Wilson commented last month, with the caveat that it could still take a few quarters to see this play out in venture capital activity.

There’s some data to support this. For example, Carta finds that total capital raised in Q2 increased QoQ. SVB (lol) suggests that we have found a floor with 2023 healthcare fundraising on pace to match 2021.

The other view is that we are positioned for prolonged pain in early stage capital markets - a multi-year “slow bursting” as Bill Gurley phrased it in a recent interview.

There are also data points supporting this view. While capital deployment may be increasing, a significant portion of recent financings are part of a “tidal wave” of down rounds. Startup layoffs, “unicorn” fire sales, and significant turnover at investment firms are widespread. In healthcare in particular, many “darling” startups of the past decade are imploding in front of our eyes (e.g. Pear Therapeutics, Bright Health, Babylon Health).

The lack of consensus is exacerbated by the opacity of private markets. Whereas public markets capitulate transparently, the dynamics of private markets have worked to conceal the reality of the private asset bubble bursting (e.g. non-disclosed insider rounds which use intricate structures to keep headline valuations flat).

Ultimately, the bearish view feels more convincing, particularly for healthcare startups. Healthcare continues to offer attractive long-term secular tailwinds and a litany of opportunities for technological disruption, but prevailing macro conditions will likely exert an outsized impact on early stage healthcare companies, which I explore in greater detail below. Investors that continue to price deals “to perfection” and fail to account for what is, in many ways, unprecedented macroeconomic uncertainty, are going to destroy a lot of value.

If you’d like to chat about this topic (or idk really anything 🥺), please don’t hesitate to reach out. Thanks for reading!

Motion in the Ocean

There seems to be a tendency for operators and venture capital allocators to look at the present market conditions as just another part of the market cycle, one that should eventually correct to the good old times. This psychology is reflected in the highly structured bridge rounds that are emerging across early stage tech, where companies are hoping to buy time until things “come back”.

But this perspective fails to capture just how fundamentally economic conditions have changed. The shift isn't simply a linear compression of risk appetites; instead, a new baseline framework for inflation and interest rates establishes an entirely different set of investment parameters compared to the previous decade. One of Howard Marks’s recent memos neatly summarizes this:

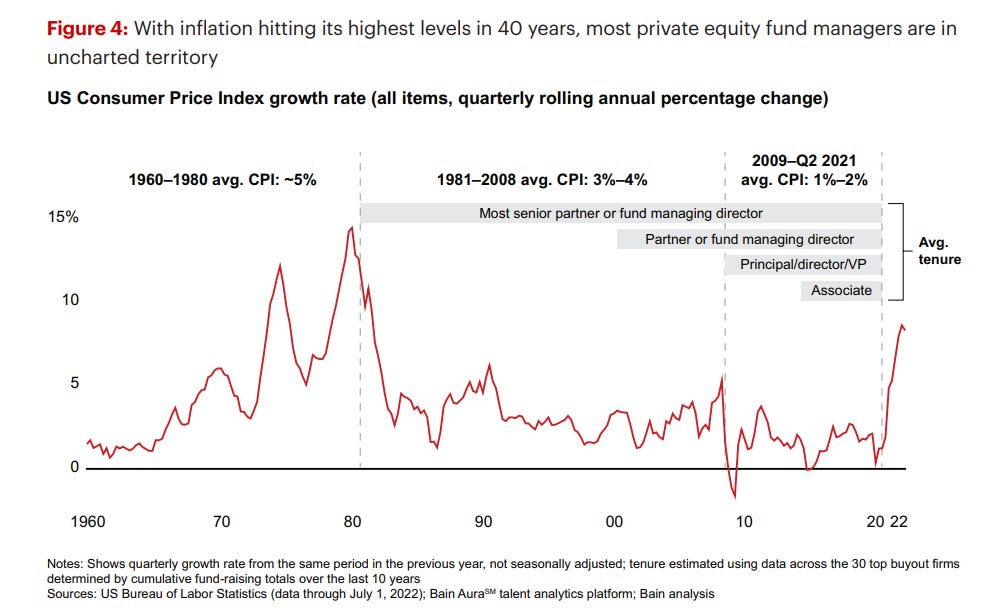

It’s hard to understate how meaningful this shift is; it’s literally uncharted territory for most professional investors.

So we’re in a new paradigm where indexing off of valuation inputs from the preceding decade does not make sense anymore. Compounding this challenge is that the near-to-medium term macro outlook seems to skew to the downside.

For all of the recent optimism around waning inflation, a “soft landing” is far from certain. Wage gains (hello UPS) and increased production costs related to geopolitical decoupling are sticky and could apply lasting inflationary pressure, long after the transient deflationary benefits of falling commodity prices and demand destruction are realized. As BlackRock explains:

We’ve moved from a regime where demand shocks dominated the macro environment to one where supply constraints dominate. These constraints … are set to stoke ongoing inflationary pressures.

This has two implications.

First, central banks will likely have to systematically hold policy tight to lean against such price pressures. That’s in stark contrast to the past 30 years when broad disinflation prompted central banks to keep monetary policy easy. And in the event that rate hikes caused financial cracks – such as the collapse of a few U.S. regional banks earlier this year – or faltering economic activity, central banks would have been quick to come to the rescue with rate cuts to help stimulate activity. See the chart. That’s no longer the case. And it is a sea change from the low interest rate environment that prevailed before the pandemic. We see policy rates staying higher for longer in major economies.

Source: BlackRock 2023 Midyear Outlook

Outside of inflation, there are other looming market risks that could impact investor risk appetite, including aging populations (which are more sensitive to inflation, thus limiting central bank maneuverability), consumer spending pressures (e.g. student loan payments resuming), and declining corporate capex/opex investments as we approach a big scary corporate “debt wall.”

These macro risks pose two broad implications for early stage companies.

First, the marginal buyer of assets is evaporating.

Growth stage funds are struggling to meet fundraising targets. Even the pLaYiNg DiFfeReNt GaMeS investors are (finally) severely marking down investments made at the top of the market. This suggests that sponsor-backed buyouts and growth rounds will be harder to come by. “Strategic” investors will also be under greater scrutiny. This means fewer M&A exits, fewer “flyer” venture capital investments, and fewer science experiments off the balance sheet in non-core categories. This is particularly impactful on healthcare where the majority of lucrative exits happen via strategic M&A. The shrinking buyer set will apply further pressure to valuation multiples, a particular concern for those venture capital firms which have built their entire models on passing off the hot potato to the next guy/gal.

The second major implication is that achieving earnings growth will be harder and harder.

Sales cycles across industries are elongating. This has a severe impact in healthcare where the sales cycles are already glacial. Indeed, all types of customers in healthcare - payors, providers, life science companies, etc. - are becoming more judicious about vendor spend. This means more small pilots instead of large first contracts. More ROI validation before customers are willing to expand. Reduced ability to count on YoY seat/license/membership expansions at growing customers as an embedded revenue growth lever.

The slow sales and implementation cycles that plague healthcare create a dynamic where compared to other industries, it just takes longer to understand if healthtech startups have achieved compelling product-market-fit. All of these macro headwinds work to make this problem worse.

On balance, this means that the filter on companies across stages will get tighter and tighter, and valuation multiples will likely remain compressed for all but the companies that have robust indications of product-market fit, attractive returns on capital, and de-risked plans on how to deploy new capital to fund growth.

For investors, this emphasizes the need for price discipline, something which venture capital firms are notoriously bad at.

Public market value investors will be familiar with the concept of investments being “priced to perfection” vs. having an embedded margin of safety. This means that even great companies can be bad investments if the entry price is too high. This also means that difficult situations can yield attractive returns, if the price is right.

If you had bought Enron equity in those days between the collapse of the Dynegy merger and the bankruptcy… you would have had over a 10X return if you [were] willing to hang on for 7 years.

Source: Acquired Podcast - “Enron: The Complete History and Strategy”

Unfortunately, due to the perverse incentives at play for most venture capital strategies, investors have been implicitly encouraged to eschew any semblance of price discipline. That’s because the conventional VC model passes the risk buck almost entirely onto the entrepreneur. I’m not sure how durable that model is going to be going forward.

Surviving the chop

Early stage healthcare companies in this environment should look to modulate fundraising and burn rate based on business model conviction.

Do you have tremendous pull from the market that you can can’t satisfy with existing infrastructure and resources? Great, then make like a beyblade and let it rip. Not there? I’d suggest calibrating very precisely around what the Company wants to achieve with the capital to avoid getting caught “over your skis” - i.e. running out of runway with no ability to tap existing investors for additional cash and not enough to show to garner outside investment interest.

In the face of elongating sales cycles and growing commercial pressures, healthcare startups that can achieve any of the following will be very well positioned to attract capital at premium valuations:

Unique distribution models that make getting to a contract an easy yes

Example*: TapestryHealth elevates the standard of care via its tech-enabled platform for SNF residents at little to no cost to the SNF owner, making it a “no-brainer” for the SNF

Legitimate validation of hard-dollar ROI, ideally with referenceable customers

Example*: Azra demonstrated in a referenceable case study with HCA the ability to identify more oncology patients and reduce patient leakage via its AI technology which reviews pathology reports

Rapid “speed-to-value” for customers to reach the stickiness stage faster

Example*: Razormetrics has emphasized rapid implementation and action yielding the ability to demonstrate ROI on drug spend for health plans and self-insured employers in <120 days (hey, that’s fast for healthcare!)

* These are all Sopris Capital portfolio companies since those are the companies I’m most familiar with

In the absence of these things, companies may find other ways to “de-risk” revenue growth. I always lqtm when I think of this tongue-in-cheek “hierarchy of disclosure.”

It’s meant to be derogatory to overpromising startups with little substance to speak of, but it’s also… kind of what early stage healthcare companies need to do? Helping investors gain confidence in customer demand is essential, and there might be creative ways to do that outside of signed contracts (e.g. validation via subject matter experts, recorded demos with folks who would be customers). Investors will (and should) haircut these efforts, but it can help build conviction on the margins.

Good times ahead…

Over the long term, there will continue to be opportunities for new companies to build enterprise value by solving acute pain points throughout the healthcare ecosystem. After all, private investments in healthcare have historically outperformed other sectors across multiple market cycles.

We can’t forget that despite representing ~20% of US GDP, healthcare has historically represented only 6% of technology spending, implying substantial underinvestment and runway for increased tech adoption (I mean, have you ever been to a doctor’s office lol).

The problem is that many investors over the preceding decade have translated the large TAM and overarching long-term tailwinds in healthcare to mean that “healthtech goes brrr,” leading to significantly overcapitalized, overvalued early stage companies forced to grow into unrealistic expectations. And often, this has come at the expense of patient care.

Failure to account for macro headwinds in investment underwriting leads to poor outcomes for all stakeholders. Investors who can exert price discipline are going to be better positioned to achieve attractive risk-adjusted investment returns while delivering on the promise of improving care and outcomes.