No Good, Very Bad Incentives

And how concentration could be a vector of differentiation in venture

The premise of VC: An American History by Tom Nicholas is pretty much that the GP/carried interest model prevalent in venture capital today is an artifact of whaling ventures in the olden times. I found this precedent hilarious and alarming from the perspective of a founder, because in this analogue their beloved company is a giant whale carcass getting hacked apart by VC’s trying to harvest some sweet, sweet blubber. Not the image that comes to mind when I think of a value-additive capital partner.

I was reminded of this history this week when Genius announced that it had been acquired for $80mm. As a frequent user of the lyrics explainer to clarify my personal “son reebok o son nike” moments, my reaction to that news was confusion, because I thought the Company was valued way higher. In fact, the Company had raised approx. $80mm in venture financing from notable investors like Andreesen Horowitz and Eminem.

I don’t know anything about the structure of capital invested into the Company, but making some reasonable assumptions, this looks like a flat out terrible outcome for the Company’s founders. If there’s >$80mm (probably more including interest accrual) of preference sitting on top of the common stock and option holders, founders / management / employees would be completely wiped out. Talk about a snap back to reality.

It’s possible that the investors put in place some kind of a transaction bonus to incent the management team to get a sale across the goal line, but any cash proceeds from that kind of arrangement are likely peanuts compared to what employees thought their equity might be worth some day. On the other hand, it actually might be an OK outcome for investors - it looks like they might recover a significant portion of their at-risk principal vs. taking a total write-off.

Abstracting away, this topical case illustrates the massive divergence in incentives between conventional VC investors and startup founders/management teams.

Incentive, Meet Outcome

When you look at the conventional Silicon Valley style of venture investing, it’s alarming how misaligned the incentives are. I’m going to oversimplify this for the sake of brevity, but the two main incentive misalignment pain points between venture capital firms and startup founders are 1) the “other people’s money” problem, and 2) the “spray and pray” problem. I’m far from the first person to discuss these so I’ll try to avoid belaboring the points here.

Other People’s Money

VC firms raise capital from limited partner investors like pension funds & endowments. VC firms make money from management fees and carried interest on that LP capital. Inherently, there is a principal/agent problem between the LP’s and the VC firms who invest on their behalf. If a VC firm does not have enough “skin” in the game, there is potential for adverse behavior from the LP’s perspective. For example, the firm might take really risky bets because their upside is really high and their downside is negligible (it’s not their principal at risk).

Moreover, VC funds need to put the capital they raise to work. This drives investors to pay premium valuations for the sake of getting deals done because otherwise the capital they raised is just sitting on the sideline (not earning fees!). They NEED to do deals. This has been exacerbated low interest rates and massive war chests raised by firms in the space in recent years.

This specific misalignment is mitigated by the concept of GP commit, where fund partners put up a % of the fund out of their own pocket (usually ~1-5% but could be more). But if non-partnered members of the firm’s investment team have no commit themselves, there’s still a big incentive alignment issue. Junior investors, particularly those that have shorter tenures at a firm, arguably have one incentive - get deals done so that they have nice logos on their resume to point to. If they’re not sharing in significant upside (i.e. carried interest) in the deal, then they probably don’t care about the outcome. Since deals are rarely attributed to junior investors, if a deal goes bad, it’s easy to say that it’s not on them.

Every member of a fund’s investment team (in any asset class) should have a material portion of their net worth invested in deals that they source/diligence/execute - this makes every investor at the firm feel the pain of bad outcomes, and also helps them share in the joy (and $$$) of good ones. An obstacle to this is accreditation rules. Accreditation rules are stupid in general, but one “no-brainer” fix to the concept would be to allow investment professionals who work for and are investing alongside an institutional investment firm to qualify as accredited investors themselves, allowing junior staff to participate without meeting the $1mm net worth or salary history benchmarks.

Spray and Pray

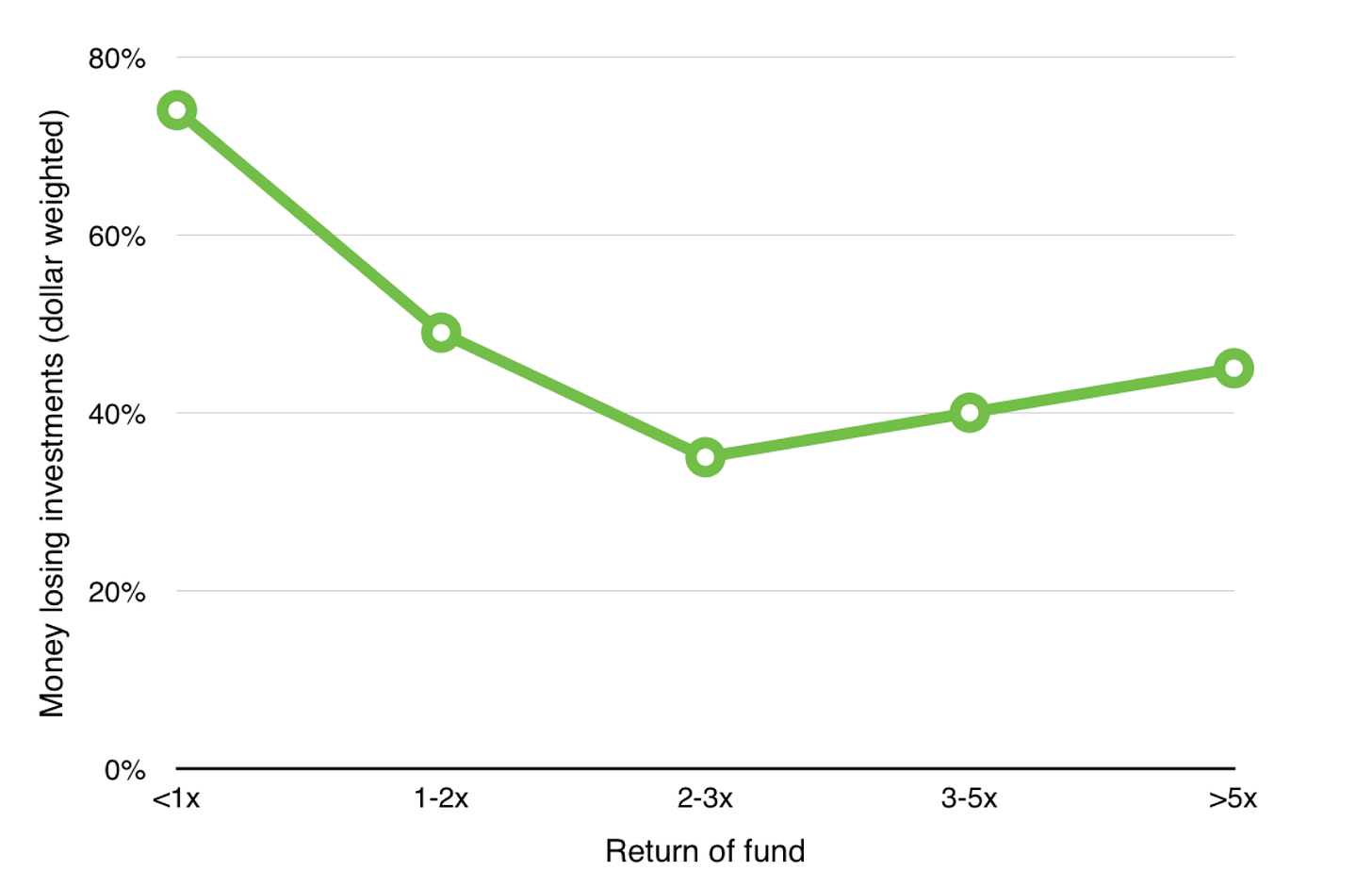

In return for the fees they earn on capital provided to them by LP’s, VC’s promise to deliver an attractive risk adjusted return on the LP capital (typically >3x return on invested capital). To hit this return threshold, most VC firms look to leverage the power law by making a ton of investments and hoping that 1-2 are huge home runs because the rest are likely to fail.

This creates a weird circularity where VC firms with this approach need to find the best companies to achieve unicorn outcomes, so they’re willing to pay a huge premium valuation on their investment, but because they just paid a huge premium valuation, only a unicorn-type outcome justifies the price they paid.

This is a perverse dynamic. A company taking investment capital from a typical VC firm must now orient its entire strategy and cost structure around being a home run. The company has now severely constrained its optionality because the road to growing slowly with less burn is closed off. It must grow rapidly or die, because rapid growth is baked into the premium valuation they’ve just raised on. Further, taking in a lot of capital creates a large preference hurdle - in the Genius example, the Company had to be worth significantly more than $80mm for the founders to see any kind of pay day upon liquidation. There’s not many paths to achieve that kind of valuation. A lot of companies probably fail because they’re effectively force fed too much capital too early; the power law becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy in these cases.

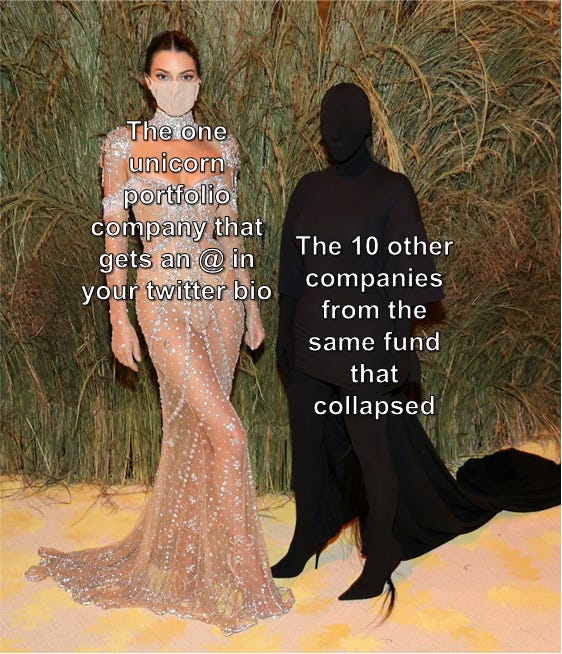

And if your company doesn’t work out, oh well - the typical VC firm has 30 other shots on goal from that fund to find a winner.

This is in diametric opposition to the risk profile of the startup founder. A startup founder has one shot on goal. Moreover, a founder has massive personal risk at stake - all of his or her reputation, time, and likely capital is tied up in the single bet they’ve made in this one company.

One could argue that partners who led a specific deal also have reputational risk on the line, but even here, the partner has many shots on goal, so the magnitude of risk is not proportional. Also, how often are startup failures attributed to firms or specific investors, vs. the founders themselves? Reputational risk is asymmetric.

#notlikeotherVCs

Over time, I think that concentration might become a differentiator for venture strategies.

This approach is antithetical to the dogma described above of needing diversified portfolios in venture to benefit from the power law. It’s exactly what you’re not supposed to do to be successful in venture.

Source: “The Babe Ruth Effect in Venture Capital” by Chris Dixon

Deploying a concentrated strategy would turn the investment model on its head. A concentrated investor would need to focus on reducing the number of write-offs in their portfolio. They’d have to be very price sensitive and have more protective terms structured into their investments.

On the face, those items don’t look attractive relative to the “easy money” from more traditional strategies. Furthermore, with these constraints in place, it’s difficult to actually get capital to work, particularly in competitive markets.

However, there is a critical advantage to a concentrated approach in that it meaningfully aligns incentives between investors and founders. That’s not important when things are going well, but is essential when things go wrong and suddenly companies find themselves way off-piste. For a founder/management team, you might want the investor that’s going to roll up their sleeves and help you overcome the adversity. That’s a tall ask for an investor that has 20 other companies they observe. So with concentration, maybe you win the hot deal you’d otherwise lose, because you can actually be a better capital partner and the risk profiles for investor and founder are closer to parity.

As venture firms position themselves to be competitive in the marketplace of capital, concentration might help investors punch above their weight.

//

Disclaimer: