Around the time I was graduating college, there was a budding trend on Wall Street called “juniorization.”

Juniorization referred to a perceived recomposition of the Wall Street workforce as younger, less experienced staff replaced older, more experienced staff.

When I first heard the term, I simply shrugged it off into the recesses of my mind and returned to devouring the remains of the septuagenarian managing director whose job I stole with my robust powerpoint logo arranging skill set.

But recently, I have been thinking about how “juniorization” is an apt description of a broad trend taking place across healthcare.

As the healthcare industry contends with a widespread shortage of physicians, so-called “mid-level” providers, like nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs) are playing an increasingly important role in the provision of care. For people in healthcare deserts, like rural regions which span 97% of the US by land, mid-level providers serve as an absolute lifeline by representing what is often the ONLY clinical care readily available.

I am super interested in this trend, having seen the impact that NPs and PAs are having across various clinical settings. Many emerging care delivery models that we evaluate at Sopris Capital rely on these clinicians to provide services cost-effectively. We’ve invested in multiple companies where mid-level providers are critical to operations, like TapestryHealth (senior care) and Mindful Care (mental health urgent care).

Continued below is some discussion on why this trend is taking place, and where I see some potential challenges/opportunities for new companies to help support a “juniorized” workforce.

There’s an APP for that

The reason this trend is taking place is simple: healthcare as an industry is being asked to do more, with less. Demand for healthcare services continues to grow as the US population ages. While the physician workforce appears to have entered an era of chronic supply shortages, the labor pool of mid-level advance practice providers (APPs) is growing rapidly. Naturally, more volume will have to shift to where the labor actually exists in order to meet demand.

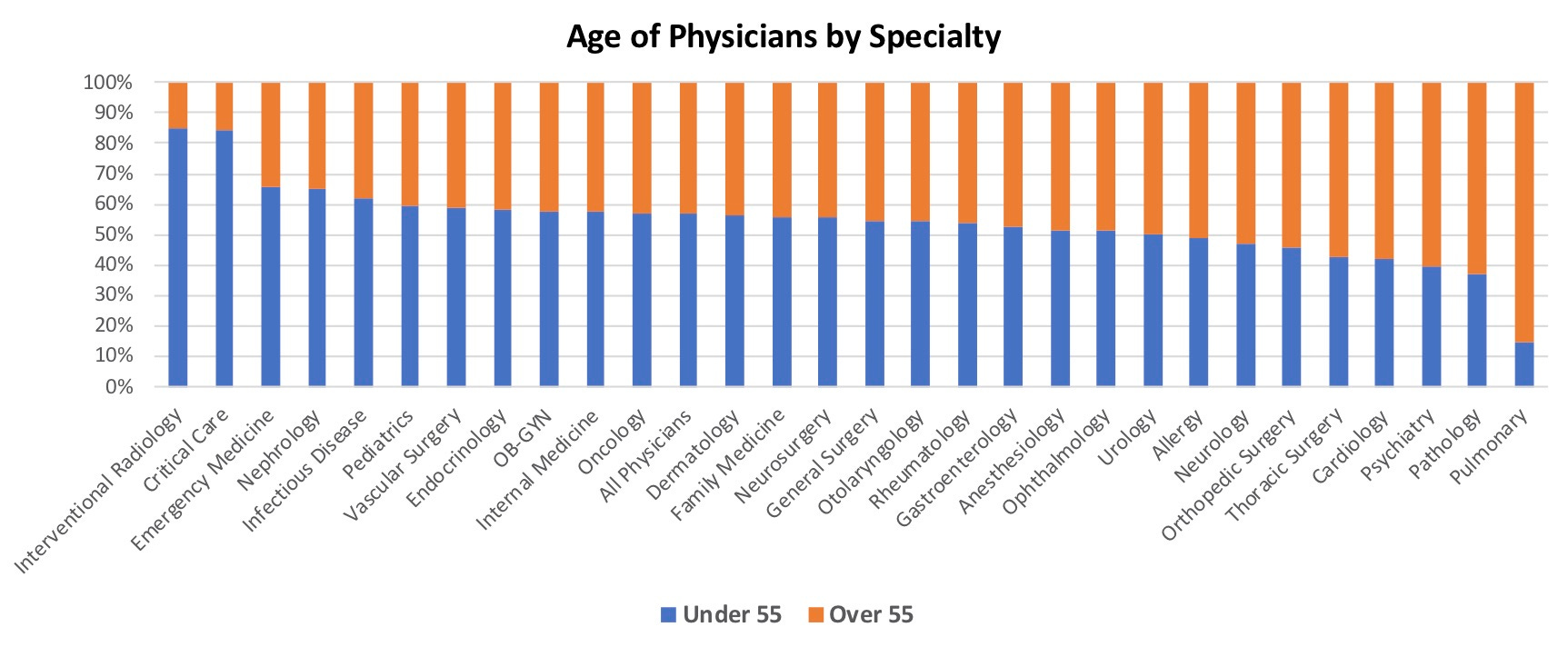

The physician workforce is quite old. For example, according to a 2021 survey, ~47% of physicians across all specialties are aged 55+, with some specialties exhibiting alarmingly high ratios1.

Meanwhile, there are not enough new doctors entering the workforce to replace aging docs as they retire. Several factors contribute to this, including long and expensive education requirements, limited residency slots, barriers to in-sourcing immigrant talent, over-indexing on specializations, and historical moratoriums on new medical schools.

Against this backdrop, APPs provide tremendous support to healthcare’s labor infrastructure. APPs are trained and scoped to deliver significant care at significantly lower cost than physicians.

A lot of physician groups will get upset and say, “Well, you know that an APP is not a physician,” and I will never say that they are. They don’t have that level of training, but the data shows they can do 85% of what a physician can do. The other 15% should be done by a physician and by elevating the complexity of what the physician does in the course of their daily work by offloading a lot of that other 85% to the APP, then we have everybody working to the top of their scope and we still increase access.

Source: Health Leadern interview with Allison Dimsdale, DNP, NP-C, AACC, FAANP

Unlike the physician labor pool, the labor pool of APPs is growing rapidly.

The combination of streamlined education requirements and an attractive ROI for prospective PAs or NPs all but guarantees that the growth of the APP labor pool will persist.

We project that these trends will continue through 2030. The number of full-time-equivalent physicians is expected to continue growing by slightly more than 1% annually, as increased retirement rates are offset by increased entry, whereas the numbers of NPs and PAs will grow by 6.8% and 4.3% annually, respectively. Roughly two thirds (67.3%) of practitioners added between 2016 and 2030 will therefore be NPs or PAs, and the combined number of NPs and PAs per 100 physicians will nearly double again to 53.9 by 2030. These shifts will probably be even more pronounced in primary care, where physician supply has been growing more slowly than in other fields and NPs tend to be more concentrated.

Source: Growing Ranks of Advanced Practice Clinicians

Bridging the GAPPs

This ongoing recomposition of the clinical workforce poses multiple challenges and opportunities. I think that the most significant pain points are in: recruiting & retention, training & development, and compliance & billing.

Recruiting and Retention

With clinical workforces acutely strained during the pandemic, technology-enabled healthcare staffing platforms & marketplaces garnered significant interest and funding over the past few years - e.g. IntelyCare, ShiftMed, ShiftKey, Nomad Health.

However, based on a quick scan of online NP/PA forums/blogs and talking to my NP/PA friends, the most common resources to find full-time APP roles are still traditional recruiters and industry-agnostic job boards like Indeed and LinkedIn. This implies that there might be room for dedicated recruiting resources for APPs, particularly tools that enable APPs to manage their own careers.

Training and Development

Given that APPs by definition enter the workforce with less experience, training should be a key focus area for organizations seeking to maximize their APP talent.

Robust training offers both a differentiator in recruiting talent and a tool to ensure that recruited providers are able to deliver high quality care. For example, Mindful Care has developed a thorough monthslong onboarding curriculum which helps new-grad psychiatric NPs ramp up in their roles within the organization.

Many forms of continuing education tools could be relevant in elevating APP talent. One emerging area that I am particularly interested in is next-generation clinical training simulations. In speaking to practicing physicians, they express consternation around the fact that APPs have substantially less clinical exposure than physicians. A lot of “good medicine,” they argue, is applying hours of experience to understand the right way to dialogue with a patient: asking questions and interpreting the patient’s feedback appropriately. This is an area where simulation technology could come into play.

Simulations offer clinicians the ability to receive feedback and guidance at an unprecedented scale. For example, medical schools and universities are already utilizing mixed-reality hardware powered by clinical simulation software like HoloPatient by GigXR to put students into real-world scenarios. The technology represents a substantial upgrade to the current standard at med schools of hiring paid actors to represent standardized patients (sorry Kramer).

These scenarios can be infinitely customizable, repeatable and scalable, advantages to even real-life patient encounters. And these simulations, which are still in the earliest innings of development, will likely become even more powerful over time as they begin to incorporate next-generation AI capabilities.

I would not be surprised if the adoption of simulation tools accelerates as organizations seek to develop their non-physician provider teams.

Credentialing and Billing

Scaling an APP based workforce introduces complexity around licensing, credentialing, compliance and billing.

States have differing regulations around the autonomy with which APPs can practice, with varying degrees of physician supervision required. Beyond state regulations, individual payors can have their own requirements around physician supervision. Navigating this complexity while seeking to maximize revenue opportunities (e.g. leveraging “incident-to” billing) creates a significant administrative burden.

Relieving the administrative and compliance burden for organizations deploying APP talent is an interesting opportunity space for new companies. For example, Zivian Health offers a platform to streamline APP/MD collaboration while helping organizations scale their supervising MD capacity. These kinds of resources should enable organizations to devote their time and attention to core operations, instead of managing bureaucratic bloat.

Insatiable APPetite

In closing, the growing role of NPs and PAs is inevitable as supply constraints force greater decentralization of healthcare. This decentralization will have impacts well beyond mid-level providers as the roles of groups like care coaches, care coordinators, and non-clinical caregivers become elevated as well.

Together, these groups will form a critical connective tissue that is foundational to US healthcare. Companies that can build solutions for the growing pains of these groups are bound to find fertile ground for growth.

Disclaimer:

This content is being made available for educational purposes only and should not be used for any other purpose. The information contained herein does not constitute and should not be construed as investment advice, an offering of advisory services, or an offer to sell or solicitation to buy any securities or related financial instruments in any jurisdiction. Certain information contained herein concerning economic trends and performance is based on or derived from information provided by independent third-party sources. The author believes that the sources from which such information has been obtained are reliable; however, the author cannot guarantee the accuracy of such information and has not independently verified the accuracy or completeness of such information or the assumptions on which such information is based.

Do any readers know why >90% of pulmonary docs are 55+? Seems like an insane ratio

That data is probably folding in younger pulmonology trained physicians in under the critical care heading, because the fellowship is now mostly a combined pulm-crit care program.

"For the 2015-2016 academic year, Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)-accredited 147 combined training programs with 1,641 active positions in Pulmonary Disease and Critical Care Medicine, and 18 training programs with 73 active positions in Pulmonary Disease alone." - Per ACP