I talk to a lot of people who want to get into venture capital. There are a lot of resources out there, but it can be hard to figure out where to get started.

One thing that I often recommend is to flesh out a list of 3-5 “favorites” in three categories: businesses, executives, and investors. I think this is a good exercise for two reasons.

First, it helps you figure out if you have enough baseline curiosity about the people and levers that drive businesses to find a VC career engaging. Early-stage investing mostly sucks. The feedback loops are super slow and mostly negative. You can develop sharp perspectives but typically lack sufficient control to action those insights. You’re constantly trying to find non-consensus alpha when it seems like everyone around you is getting rewarded for indexing whatever prevailing trend is taking shape at the time. To power through the slog, you have to become a pure simp for capitalism, so that at least you might be able to relish the journey. This exercise is a good barometer of this specific type of curiosity.

Second, the exercise forces you to think in narratives. All investing is grounded in storytelling, and this is doubly true for early-stage investing which is data sparse to begin with. When you build a list of people and groups you really admire, it forces you to think about telling the story of why they are so interesting, which is a fundamental muscle you want to develop because it informs almost everything - sourcing companies, pitching them to your team, pitching them to potential partners/customers, recruiting talent for them, selling them.

So in essence, it’s about figuring out if you find the stories of company building interesting and if you want to tell those stories every day. With that context, the Mt. Rushmores of companies/executives/investors that you pick don’t have to be the most “successful,” just ones that you are fascinated by. And you don’t really have to be fascinated by every aspect of their existence - even 1-2 things that you really find fascinating about them is enough.

I get that it feels weird to fawn over the accomplishments of people that in a macro sense are sort of your peers. But I figure that most very successful people are students of their game - why shouldn’t you be a student of yours?

This idea has come up a few times for me in the last month, so I decided to put mine down on paper, mostly for my own benefit. Hopefully you find it interesting too. For my little Mt. Rushmore of each category, I tried to pick 3 “conventional”/well-known names and then 1 less obvious name to mix it up because I’m just so fun and random like that. I started drafting this out and it got super long, so I’m going to break each category into a separate post, starting with four companies I’m fascinated by.

My picks are as follows (drum roll please):

Very Fascinating Businesses: Costco, Epic Systems, Renaissance Technologies, Major Food Group

A little more on all of these follows.

I’d love to hear who you think merits Mt. Rushmore consideration if the concept resonates with you. Anyways, thanks for reading ✨✨.

I. Businesses I Am Fascinated By

Costco

Fascinating because: Costco is a great example of how single-mindedness of purpose drives operational clarity, which in turn has enabled the brand to bleed into the identity of its customers.

Costco is my favorite company. There are so many aspects of the operation that spark joy on which a ton of ink has been spilled - market leading comp for employees, promoting from within, flexing its leverage on suppliers and passing on the savings to customers, the curated SKUs, the absurdly accommodating return policy, the treasure hunt experience, the $5 chicken!

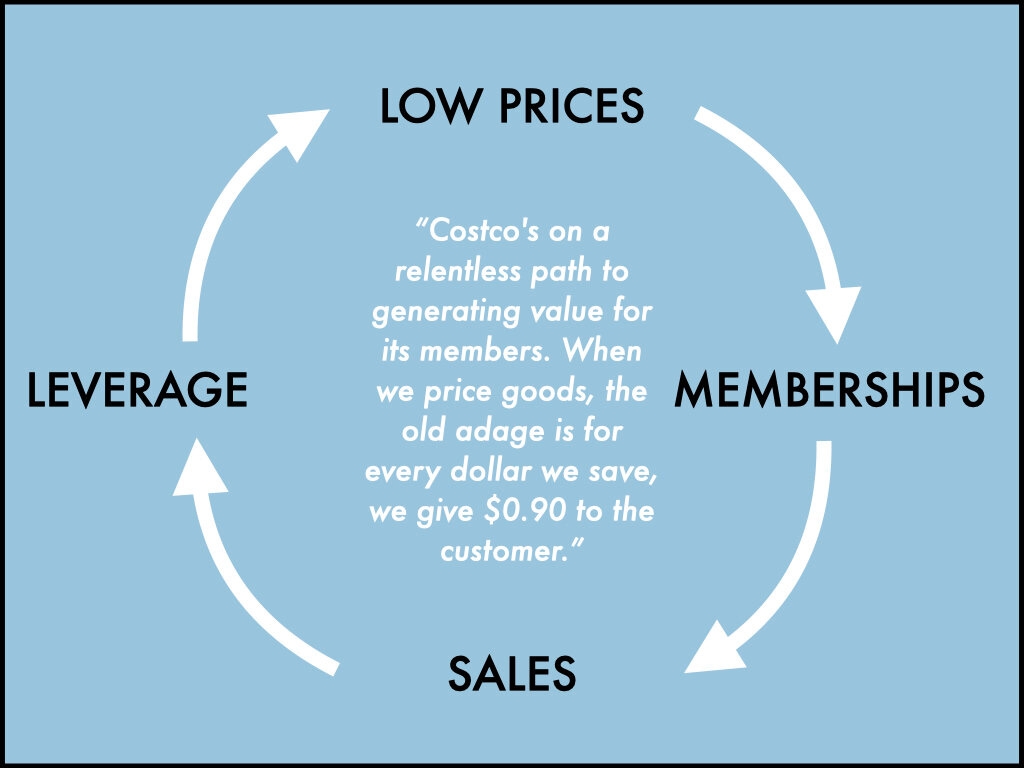

The unifying thread across these operating principles is a fanatical focus on delivering customer value. This single-mindedness does two important things.

One, it clarifies every business decision. A sacred North Star provides a precise scale by which to weigh costs and benefits. In Costco’s case, the North Star is simply what will make the membership more valuable.

Second, this single-mindedness expressed over and over across so many facets of the business engrains this message into the minds of customers. And it is done so effectively that I think Costco achieves something very unique in business - it transcends into the customer’s identity layer. People don’t just shop at Costco, they are Costco Shoppers. Being a Costco member conveys something fundamental about people’s values - that they care about quality and value, ideas which have universal appeal, including and especially for Costco’s relatively affluent customer base. Very few brands achieve this.

Perhaps this is why the wholesale-core Kirkland Drip trend emerged - we are dying to show people that we’re not like regular consumers, we’re cool value-conscious consumers 😎.

Epic Systems

Fascinating because: Epic is an incredible example of building a dominant company “brick-by-brick.”

It blows me away how under-the-radar Epic is outside of healthcare circles. It is probably one of the most successful technology startups of all time. Its dominance is so prolific that Bill Gurley gave an entire talk complaining that Epic’s success surely must be the nefarious result of regulatory capture.

Epic, like so many successful startups, is wholly shaped in the image of its founder Judy Faulkner:

Faulkner, a computer programmer who founded Epic in a basement in 1979, has bucked convention from day one, starting with the company dress code: “When there are visitors, you must wear clothes.”

While competitors like Cerner (now Oracle Health), Allscripts (now Veradigm) and Athenahealth, grew by taking venture capital money, executing mergers and acquisitions, going public and then private again, Faulkner has eschewed any outside interference. This mentality is enshrined in the first two of Epic’s Ten Commandments, which hang on the wall in a campus bathroom:

Do not go public.

Do not be acquired.

…

Faulkner has retained all of Epic’s voting shares, which, upon her death, control will be shifted to a trust governed by four of her family members – her husband Gordon, 80, and three children – and five long-time senior manager employees at Epic. In line with Epic’s Ten Commandments, she says the trust rules prohibit an IPO, sale or acquisition, and stipulate that the next CEO “has always got to be a long-term Epic employee and a software developer.” A separate oversight board of up to three of Epic’s long-time healthcare customers will serve as trust protectors and “sue anyone who doesn't vote according to the rules.”

Source: Forbes

In a market characterized by mass consolidation via M&A, Epic has never made an acquisition. Not one. The graphic below comparing the origin/history of Allscripts/Veradigm vs. Epic highlights this insane dynamic:

This in-house, full control mentality is central to what Faulkner says sets Epic apart from its competitors: Since Epic has never acquired another company, it hasn’t had to build bridges to interface from one type of software to another.

Source: Forbes

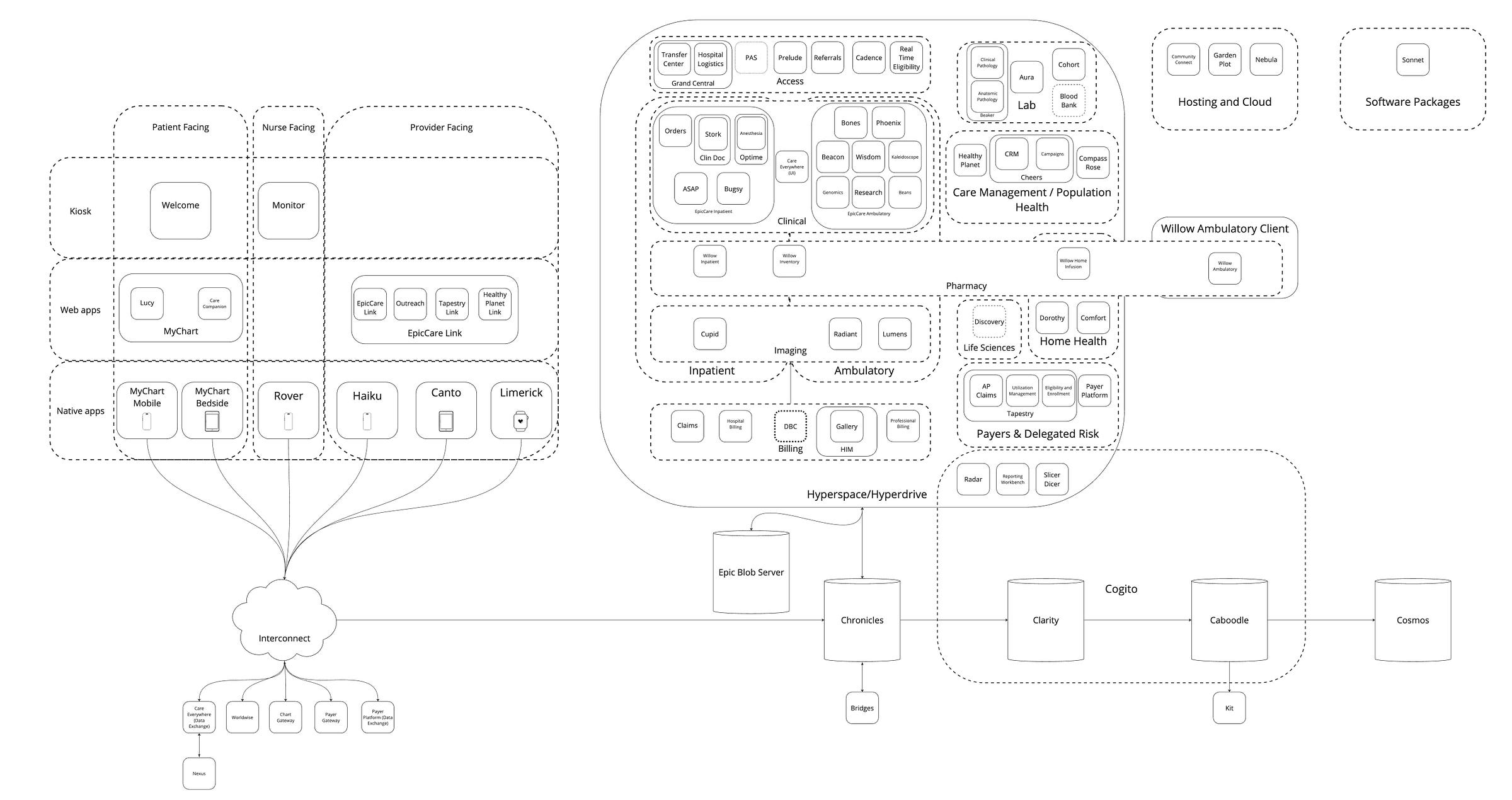

Mapping out Epic’s fully-integrated ecosystem further emphasizes the point - as illustrated by Brendan Keeler:

Epic's monolithic architecture is truly a wonder to behold, allowing for tight integration between different modules and ensuring data consistency across the entire system. Notice in the diagram how all applications and modules are built on that same underlying database (Chronicles), using a shared data model:

…Epic's dominance in healthcare IT is no accident. Moreover, it’s not the result of nefarious covert operations and market manipulation. It's the result of a carefully crafted strategy that leverages integrated systems, network effects, a weak and diminishing pool of competition, and a deep understanding of healthcare's unique needs. From its monolithic architecture to its community-wide interoperability through Care Everywhere, Epic has built a system that's more than the sum of its parts.

Source: “An Epic Saga: The Origin Story” by Brendan Keeler / HealthAPI Guy

In short, Epic’s success is not regulatory capture - it is a masterclass in developing durable moats and network effects through thoughtful strategy, focus, and execution. The dedication required to ignore the noise and keep building brick-by-brick is truly remarkable.

Renaissance Technologies

Fascinating because: Renaissance Technologies (“RenTech”) is a fascinating case study on the power of compounding small advantages over time and incentive design for human capital.

RenTech merits fascination based on performance alone - the sheer consistency of market-beating returns from its flagship Medallion fund is mind-blowing:

I have RenTech in my fascinating company bucket rather than the fascinating investor bucket because it is the system/organization that I find so uniquely compelling vs. the raw investment approach.

First, if we take founder Robert Mercer at his word, the Company’s outperformance illustrates a really simple insight that applies broadly to basically all of life: a slight advantage compounded over a sufficiently large number of iterations yields significant returns. That’s it, that’s the whole model.

“We’re right 50.75 percent of the time . . . but we’re 100 percent right 50.75 percent of the time,” Mercer told a friend. “You can make billions that way.”

I find this concept existentially soothing. You don’t have to win every time or dominate every single situation (you couldn’t if you tried). Rather, the key to success in so many disciplines from professional investing to professional poker1 is to build a slight edge and then just give yourself enough reps/iterations/time to have the odds compound in your favor, outlast competitors, and deliver big outcomes.

The second thing that is super interesting about RenTech is how they have architected a system of financial incentives to keep new generations of talent hyper-motivated to continue delivering this performance. Ben and David from the Acquired podcast make the case really well in their episode on RenTech:

David: … I think the third puzzle piece of what makes RenTech so unique and defensible is Medallion’s structure itself, that it is an LP-GP fund with 5% management fee and 44% carry.

…

David: It’s all themselves, it’s all insiders. Why do they charge themselves 44% carry and 5% management fees? I think Jim [Simons] talks about this that, oh, I pay the fees just like everybody else.

… What is happening here? Okay, here’s my hypothesis. This is not about having crazy performance fees. This is not about having the highest carry in the industry. This is a value transfer mechanism within the firm, from the tenure base to the current people who are working on Medallion in any given year.

Here’s how I think it works. When people come into RenTech, they obviously have way less wealth than the people who’ve been there for a long time, both from the direct returns that you’re getting every year from working there and just your investment percentage of the Medallion fund… If you work there, your 401(k) is the Medallion fund…

Given that, though, how do you avoid the incentive for a group of talented younger folks to split off and go start their own Medallion fund?

Ben: Especially when they all have access to the whole code base. The whole thing is meant to function like a university math department, where everyone’s constantly knowledge-sharing because we’re going to create better peer-reviewed research when we all share all the knowledge all the time. You would think that’s a super risky thing to give everyone all the keys.

David: … Let’s round that up and just add them and say 49% [5% mgmt + 44% carry] of the economic returns in any given year go to the current team, and 51% of the economic returns go to the tenure base.

What is the equivalent here? I think it’s like academic tenure kind of thing. The longer tenure you are at the firm, the more your balance shifts to the LP side of things…

Ben: Essentially David, the real magic is they’ve got one fund, it’s evergreen, and when you start at the firm, you’re only getting paid the carry amount, but over time you become a meaningful investor in the firm and you shift to that 51%. You’re the LP, and then over time you eventually graduate out entirely and you’re only an LP.

Source: Acquired

Incentives design is so critical to investment structuring and scaling an organization. As the great Mungerism goes - show me the incentive and I’ll show you the outcome. RenTech is a great example of utilizing incentives design to protect its moat.

Major Food Group

Fascinating because: Major Food Group (“MFG”) illustrates the power of extreme attention to detail to cultivate hospitality, a concept that is fundamental to all commerce.

The success of MFG is particularly interesting to me because it has been achieved in a conventionally terrible business - restaurants. The MFG empire now spans the globe with dozens of well-executed concepts with dedicated followings. They’ve started membership clubs where eyewatering fees yield members the perk of getting preferred access to other MFG restaurants so they can give MFG even more money. They’re even building a branded residences here in Miami. Soon you can literally live at Carbone (personally I’ve been yearning for my nights to be more Dionysian).

Why are they so successful? How are they getting people to gladly fork over $50 for a little spicy pasta?

When you ask people why they enjoyed dining at Carbone or another MFG restaurant, people often talk about “the vibe” just being awesome. I think that’s important. Studying MFG’s approach, “the vibe” is actually the culmination of an extreme, systematic attention to detail iterated across the entire customer experience. In this interview from 2021, Mario Carbone talks about his approach to opening The Grill in midtown NYC which emphasizes this hyperfocus (starts at 30:45):

If you inundate the customer with all of these textural decisions that you’re making, and if you made them with a single perspective and story in mind and you chose all of those things with that story in mind, whether they know it or not they can’t help but feel it and be part of it” - Mario Carbone

This is such an important idea I come back to a lot. I think basically every single business is a hospitality business. Even the technology and healthcare services business I invest in at work are fundamentally about hospitality. I’ve seen over and over again that customers don’t really buy products and features, they buy trust in a counterparty that makes them feel understood and is energized to solve their problem. Delivering that feeling, “the vibe,” to customers across every touchpoint seems to be what sets great sales teams apart, especially in the early stages of a Company’s commercial life. Thus, I’m super fascinated by groups like MFG that have systematized the vibe.

“We see our customers as invited guests to a party, and we are the hosts.” - Jeff Bezos

You’d best believe in the feelings economy folks, you’re in it 💫🪐✨.

I thought of this after reading “The Professor, the Banker, and the Suicide King,” which is about banker Andy Beal (fascinating in his own right btw) and his yearslong ultra high-stakes poker games with some of the best players in the world. The book describes how poker pros use this strategy to build their bank roll. Basically, you work to build a slight advantage such that you know you can win an outsized portions of hands at a given level of difficulty (say the $1/2 blind table which should have “easier” competition than the $5/10 blind tables). Given enough time at that table where you have a slight advantage, the pros are able to readily build their stack.