"Forward Deployed"

Linguistic voodoo, or the future of work?

What’s In A Name?

Titles can have a magical impact on the perception of a job.

Banks have armies of “vice presidents.” Venture capital firms hire recent college grads as “partners.” I, for one, folded clothes and rang up customers as a lowly JCPenney “customer service associate” when my peers across the mall were doing the same thing as “models” for Hollister and Abercrombie. Now I’m forced to toil in the thinkpiece mines, groveling for Substack likes to feed the crater this left in my ego 😔😔.

But perhaps the most striking recent example of job title alchemy comes from Palantir and their “forward-deployed engineers” (FDEs). Here is the origin story, straight from Palantir CTO Shyam Sankar:

In 2006, Alex Karp asked me if I knew why French restaurants were so good. I had no idea. He told me that at a French restaurant, the wait staff is actually part of the kitchen staff. They intimately understand the food, the methodology, and the technique. They are not merely carrying the food from the kitchen to the table, but are instead part of a subtle and complex system that affects kitchen operations. He wanted me to build that, but for engineering.

I did just that, and in 2007, I gave it the name “forward deployed engineering” (FDE) in homage to our customers.

FDEs embed alongside our customers and work to ensure our software solves their problem and not some proxy for their problem...

Just like French restaurants don’t blindly hand off food from an uninformed waiter to the diner, we didn’t believe in throwing our software over the wall in the hopes the customer would divine the correct meaning from it.

Source: “The Primacy of Winning” by Shyam Sankar for Pirate Wires

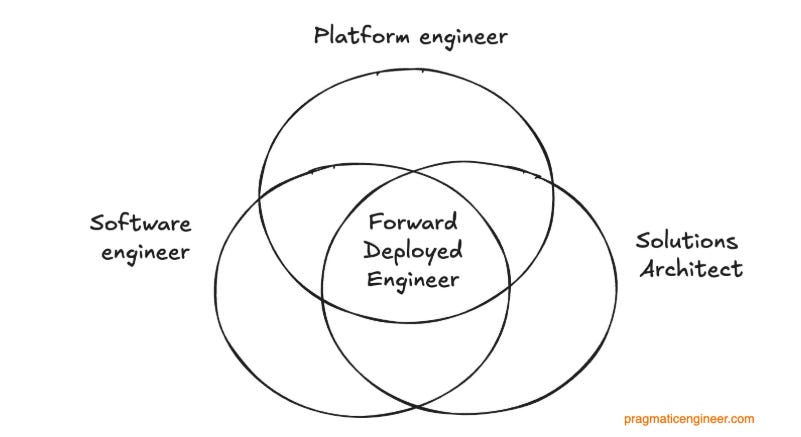

Gergely Orosz does a nice job of demystifying the concept:

Job adverts for FDEs describe a few main characteristics:

Software engineering basics…

Collaborate with Sales to close customers… Basically, when a customer is undecided on whether they can effectively use a product, Sales offers to provide an FDE to help them successfully integrate it.

Embed into customers’ teams… It’s pretty standard that the job involves travelling to customers to sit alongside them a few times. Palantir expects around 25% of FDEs’ time to be spent onsite with customers, and healthcare AI company Commure estimates up to 50%…

Contribute to the core product, and embed with core product engineering teams

Help customers succeed. The core of the role is to make customers successful by building on top of a company’s product offering

Source: The Pragmatic Engineer

The FDE role can be a source of significant consternation for investors - particularly for Palantir bears who see the company as little more than a zhuzhed up consulting firm. This high-touch, embedded services layer contradicts the dogma for “pure-play” software companies, where the goal is to minimize labor inputs to the delivery model. In their defense, what exactly is the difference between “help customers succeed” and “customer success?”

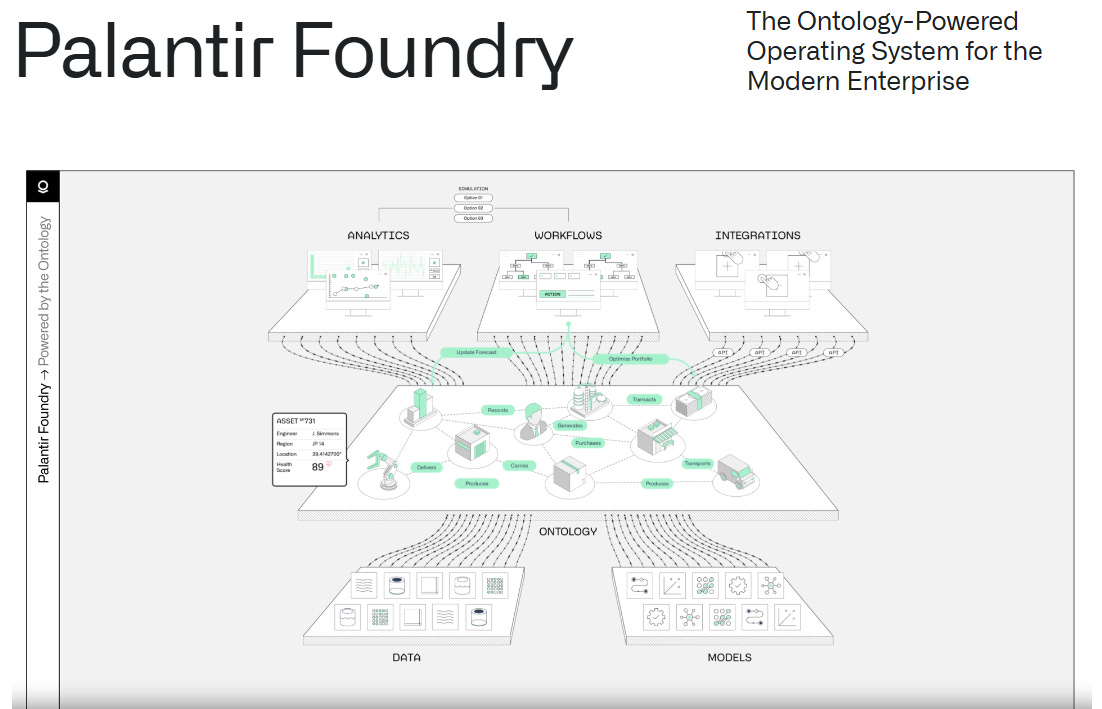

Palantir, for its part, points to FDEs as one element of a complex ecosystem of internal infrastructure, workflows, and processes that together form a “platform.”

It’s hard to argue with the results - Palantir seems to have outrun the “glorified consulting firm” allegations. While leading public technology consulting firms trade around 2x revenue, Palantir, backed by superior fundamentals and perhaps a touch of memey-ness, trades at ~100x revenue.

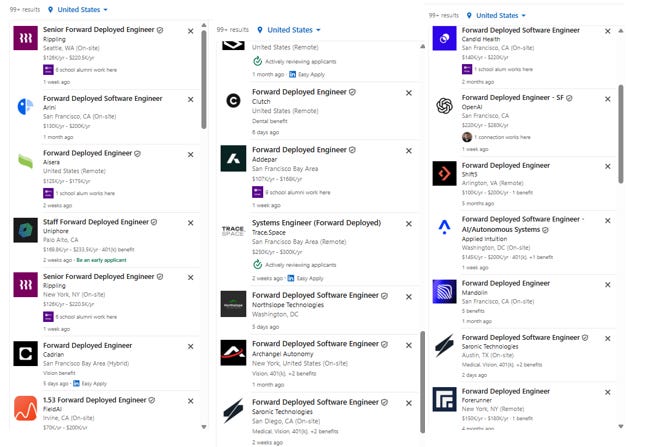

Meanwhile, FDE roles are exploding in popularity as they become woven into the fabric of prevailing technology delivery models.

This trend has legs. The idea of using a high-touch approach to implementation and value-creation seems like it will be critical in the next wave of AI adoption. Nestled in the recent, highly publicized “95% of AI is failing to deliver any ROI” MIT report is an important caveat:

Organizations stuck on the wrong side continue investing in static tools that can't adapt to their workflows, while those crossing the divide focus on learning-capable systems.

Source: MIT NANDA

The idea of “learning-capable” solutions mapped to existing customer workflows is practically a bat signal for FDEs.

It’s worth mentioning that AI businesses have (for now) inherently weaker economics than traditional software companies - inference compute costs represent a meaningful variable COGS item. The trade-off for lower gross margins is that AI tools should be able to capture more of the “work” happening across enterprises today. Said differently, applied AI companies are chasing a bigger pie than traditional SaaS firms that should yield more overall gross profit dollars. But to get that extra share of work, they have to do more hard stuff - and to do more hard stuff, they need a more flexible delivery model. As such, the demand for FDEs probably increases as AI applications permeate the market.

Valuation Considerations

The trick for founders is structuring FDEs in a way that reinforces a platform story rather than a services one. Here are some areas worth scrutinizing.

Contracting Discipline

What’s actually in the contract language? For SOWs and purchase orders, is spend delineated between software licenses and human resources? If so, then a probing buyer might ascribe a sum-of-the-parts valuation credit to that book of business. In contrast, if customers are paying for an all-inclusive package or specific outcomes and deliverables, it’s easier to justify that they view the offering as a platform. Are the contracts long term (e.g. 12-months or longer with defined renewal criteria)? Or are they short-term projects? The latter is going to be priced at a significant discount by investors, even if they are “recurring” in nature.

In a frothy market, investors and buyers tend to squint and call everything “ARR.” If the luster on AI companies fades in future years, we can expect investors and buyers to evaluate revenue quality more tightly, with contract language serving as the source of truth.

Technology Leverage

How exactly are FDEs using the core technology platform to deliver more value to customers? Often, this looks like faster speed-to-implementation and quicker time-to-value realized through the platform.

How much custom development by FDEs is reused and resold to other customers versus delivered as one-off, bespoke customization? For great platform companies, a track record often emerges quickly, showing that modules have been resold across multiple logos.

Complexity as a TAM Unlock

Perhaps the biggest advantage of the FDE model is that it allows a vendor to absorb more complexity on behalf of the customer. Good platforms will have a clear story around how FDEs expand TAM. For example, there are some customers that lack the ability, bandwidth, or appetite to consume software on a self-serve basis (e.g. biopharma companies notoriously prefer hands-on vendors). Moreover, amid a massive technology shift, customers are increasingly looking for vendors to serve as trusted thought partners rather than merely selling something off-the-shelf.

In other categories (e.g., government end markets), the complexity is so daunting that it’s impossible to serve customers without significant custom buildout. In these cases, there’s a clear story about using high-touch labor resources to configure the “platform” at the edge and meet customers where they are.

Show Me the Money

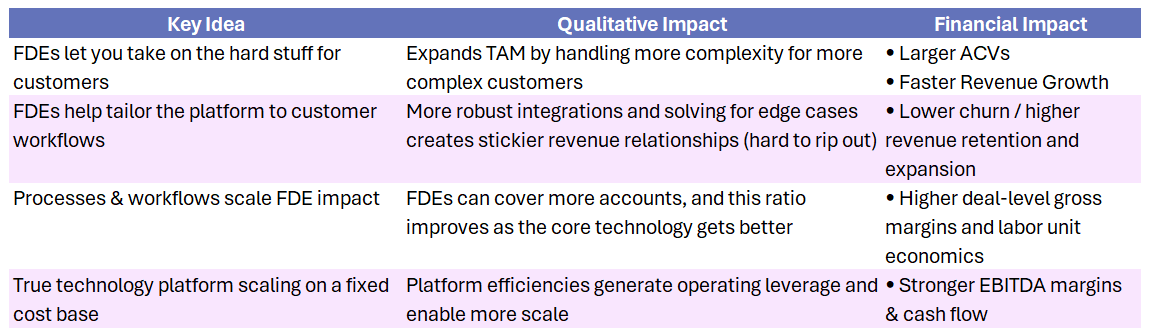

Ultimately, if FDEs deliver clear advantages, it will show up in the financials. The path looks something like this:

Applied AI companies and other FDE-led businesses will face the same kind of scrutiny SaaS companies have endured over the last decade. Well after the peak of AI-bubble mania fades, I expect that the market will continue to reward companies for retention, unit economics, and scalability.

Ambitious AI companies that build for long-term financial viability from inception will outlast hype cycles and command premium valuations over the long haul.