Increasing Complexity in Biopharma Research

The clinical, operational and market complexity which plagues biopharma research is intensifying. Can technology help stakeholders navigate the chaos?

Clinical trials are plagued by a disorienting level of complexity.

If you spend even 30 seconds learning about the present state of the biopharma research industry, you will undoubtedly hear: “80% of clinical trials fail to meet enrollment targets on time.”

This frequently parroted statistic offers an unfair characterization of the clinical research industry.

Rather, the fact that research stakeholders - including pharma and biotech companies (research “sponsors”), contract research organizations (CROs) and research sites - do successfully enroll 1 out of 5 trials in light of the multiple layers of complexity that they have to deal with is a miracle.

It’s like MLB batting averages - numerically low success rates can still be impressive when the underlying thing is hard to do. And research stakeholders are doing the equivalent of stepping up to the plate blindfolded with their arms tied together and a pool noodle for a bat. Oh, and they’re on fire.

Why are modern trials so complex? For starters, we could say that clinical research just is inherently complex. Consider a few of the deeply intertwined activities that take place across the life of a trial:

Pharma and biotech sponsors must design trial protocols that are specific enough to support the clinical goals of the trial, but flexible enough to accommodate recruitment targets and proactively avoid protocol deviations in deployment

Trial sponsors need to decide which sites to partner with and where/how to deploy the trial

Patients need to be identified, matched to trials, screened and enrolled

Participants need to adhere to the trial activities delineated in the protocol, often in spite of hurdles like transportation and costs

All of these activities are intertwined - e.g. poor site selection could lead to delays in meeting enrollment targets, poor protocol design could lead to expensive and time-consuming amendments down the line.

On top of the inherent hurdles to running a clinical trial, I see three prevailing layers of complexity at work:

Clinical complexity

Operational complexity

Market complexity

What alarms me is that across these three areas, signs point to clinical trial complexity increasing in the coming decade.

At the same time, increasing biopharma research complexity should serve as a tailwind for emerging clinical development technology companies. Specifically, companies that deliver technology in a way that actually reduces site/sponsor burden have promising outlooks. As an investor in the space, I’m optimistic about what the next decade of clinical research infrastructure “modernization” could yield, to say nothing of the transformative advancements in human progress that better infrastructure could unlock.

More on the drivers of this complexity wave and potential advancements towards modernized clinical research infrastructure follows below. As always, thank you for reading and drop me a line if this is interesting to you (📧 vpradhan@sopriscapital.com).

Clinical complexity

I think of clinical complexity as the challenges associated with designing a scientifically meaningful trial.

Data suggests that trial designs are becoming more complex. For example, IQVIA tracks a multi-variate complexity “index” metric which serves as a proxy for industry-wide trial complexity. This index suggests that trial complexity has steadily climbed over the past decade.

One key driver of protocol complexity is the number of endpoints being measured in the trial. For example, a study from Tufts University’s Center for the Study of Drug Development (CSDD) reports that the average number of endpoints measured in a Phase 3 trial has increased 37% since 2015.

Why are trials measuring more stuff? Some reasons include:

Increased focus on capturing patient experience and quality of life measures as relevant trial endpoints

Increased focus on precision medicine, which requires more endpoints as sponsors seek to stratify participants based on biomarkers, genetics and other factors

Increased use of composite endpoints, where multiple primary endpoints are combined to measure outcomes

The focus on these drivers is likely to intensify.

For example, patient experience and quality of life measures will be critical as pharma and biotech companies navigate increased price scrutiny, as positive data in these areas can greatly strengthen the positions of biopharma companies in price negotiations. As sponsors seek to make more progress in precision medicine, particularly in areas like oncology, the need for granular patient stratification will increase.

Another driver of clinical complexity is eligibility criteria for a trial. Here, we see additional evidence for increasing complexity. For example, industry-wide there is a major focus on driving greater diversity in trial participant populations. This is great, because poor representation in clinical research has historically led to major issues and consequences for patients.

But increasing representation in research appears to be much easier said than done - whereas discussion around greater diversity in trials has been prevalent over the past decade, data suggests that Black and Hispanic trial participation rates have actually declined over that period.

While challenges around representation extend far beyond protocol design, recent FDA guidance suggests that eligibility criteria (even if ultimately broadened to include more participants in line with the guidance) will require greater scrutiny.

Across multiple vectors, the clinical complexity involved in designing a trial protocol is trending up.

Operational Complexity

As illustrated in the graphic below, clinical trials face a multitude of logistical challenges.

An emerging theme in clinical trial operations is the idea of making trials more “patient-centric” so that it is easier for patients to participate in trials.

“Traditional” site-based trials present several logistical hurdles to participation for eligible patients. For example, according to Antidote, an estimated 70% of potential clinical trial participants live more than two hours away from a study center. This is a huge problem - if it’s hard for patients to get to trial activities, recruitment and trial adherence declines.

In recent years, fully decentralized or virtual trials (DCTs) emerged as a potential answer to the patient-access challenges of site-based trials. The idea was that if trial activities could be coordinated outside of the confines of a research site, then the geographic reach and success rate of trials should increase.

Unfortunately, as many folks in the industry will have seen firsthand, the promise of fully decentralized trials did not really pan out, in no small part due to the logistical issues of delivering a successful trial. For example, a recent survey by Health Advances found that clinical research executives “tend to be disappointed by DCTs’ ability to increase patient retention because the reduction of in-person visits can make it more challenging to identify and course-correct non-compliant patients.”

But despite the areas in which fully-decentralized trials fell short of expectations, executives seem to acknowledge that the future of trials will be “hybrid” and will entail more decentralized activities.

Decentralizing the activities of a trial creates new challenges. For example, questions surround how to collect and manage data from patients outside of the clinic, how to create touchpoints with clinical providers when necessary, and how to manage distribution of trial supplies. In effect, a focus on patient-centric trial design has created a last-mile delivery problem for research stakeholders, who have been left to figure out how to cobble together various assets (e.g. wearable devices, mobile clinics, in-home visits) to assemble a viable trial.

In addition, decentralized trial activities could create new data management problems for trial stakeholders.

“A remote or virtual trial introduces other solutions that are now sources for data, and all of that has to be integrated and managed… Somewhere along that chain of support in executing a protocol will be people who are charged with ensuring the quality and integrity of the data that’s gathered… It’s pretty remarkable how many different sources are now contributing data that have to be curated, compiled and then turned into an analysis data set.”

Source: Centerwatch

Great advancements have taken place over the past several years in developing clinical-grade digital measurements that can be used in trials. This is exciting, because it opens up the frequency and types of data that could be collected from patients, making research outcomes more robust. But deploying those measurements and effectively managing the data is yet another area where research complexity is likely to increase.

All told, operational complexity looks to be trending up too.

Market Complexity

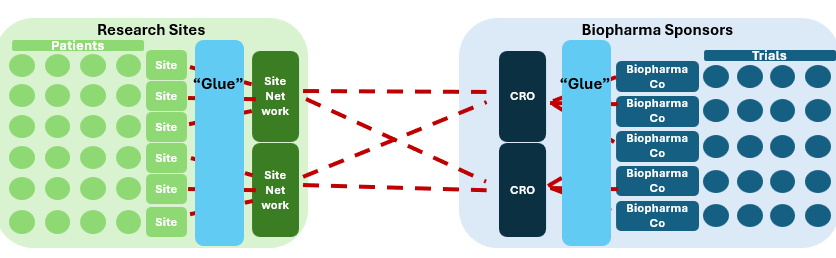

At a high level, the clinical research market seems like a straightforward two-sided market.

Like many two-sided markets, greater fragmentation means more complexity. And clinical research sites are highly fragmented.

So if you’re a pharma company trying to connect into a specific site (or vice-versa), the landscape looks more like this.

Oh and by the way, you have little to no visibility into the patients at the sites, making it hard to decide which sites to engage. Most sponsors have to figure out which sites to engage with non-clinical performance proxies at best and pure guesswork at worst.

Fragmented landscapes often trend toward consolidation - the resulting scaled operators theoretically benefit from efficiencies and economies of scale. Sure enough, on both the supply side (sites) and demand side (trial sponsors), forms of aggregation have certainly emerged - e.g. site networks and CROs, respectively. In theory, this should reduce complexity because it reduces the disparate touchpoints between the two sides of the market.

But this is only the case if supply (different sites) and demand (different trials) can be effectively integrated. In practice it looks like the aggregators have simply ingested the complexity themselves, with efforts to actually reduce complexity through integration falling short.

For example, private equity backed site-network platform Cenexel reportedly tested the market for a potential exit earlier this year, seeking a >$1bn valuation. Instead, according to Axios, the platform met resistance from prospective buyers due to insufficient integration:

“…prospective buyers are concerned about CenExel's business not being integrated enough… One source says CenExel hasn't invested enough into its technology backbone, with the business having "seen lots of EBITDA adjustments."

Source: Axios

Why is this complexity-reduction-via-integration approach so difficult in practice?

Take an example of a site network trying to understand the patient census spread across its different sites. An emerging trend in the industry is the recognition that patient electronic health record (EHR) data could have valuable insights for research stakeholders. Theoretically, a site network should be able to access the EHR data of its patients to determine how many patients they have that are eligible for a given trial protocol. But individual sites in a site network often have disparate systems - e.g. sites utilizing different EHRs that do not connect to one another easily.

This makes it nearly impossible to have the kind of real-time, single source of truth that would streamline the market complexity of clinical research. This means that consolidated groups can actually be more complex to run than if you ran a standalone site with a single set of systems.

This matters in particular because M&A consolidation of research sites has exploded in the last decade.

In many ways, clinical research sites are ripe for the private equity playbook:

Acquire sub-scale assets with predictable/proven financial profiles at attractive multiples

Drive financial improvements through the asset base via enhanced operations and economies of scale

Achieve multiple arbitrage through enhanced scale at exit

The highly fragmented landscape dominated by standalone research sites suggests that there is still massive runway for continued consolidation.

But if these roll-up platforms cannot adequately integrate assets, we can expect the prevailing market complexity to persist, if not compound. On the other hand, this suggests that PE-backed platforms that do leverage technology to integrate their networks will be positioned to maximize value at exit, and should prioritize this as part of their value-creation strategies.

Complexity as a Tailwind for Technology Adoption

This dynamic of rapidly increasing complexity in clinical research should set up the playing field in favor of emerging clinical development technology companies that promise to help research stakeholders simplify this chaos.

And yet, in speaking to sites and sponsors, a paradoxical view emerges in which there is simultaneously:

Whitespace for technology adoption (tons of “pen-and-paper” work taking place)

Technology vendor fatigue burdening research stakeholders

Here’s a great perspective shared by Jeff Kingsley, Chief Development Officer of Centricity Research:

As protocols continue to grow more complex, scaling requires greater specialization and increasingly sophisticated tech stacks. Jeff explains, “We still have lots of (tech) players in the space, which makes life harder for the site. More usernames and passwords are just the tip of the iceberg. The bigger issue is that when you have to be 'adept' at using numerous platforms, the reality is that quality and efficiency suffer because you can’t be proficient in 14 different systems.” It seems that a major challenge is the lack of good guidance.

Lack of guidance spills into every task, creating non-value added work, without regard for the reality that sites run more than one study at a time. Jeff illustrates, “I get messages like, ‘I need you to sign on to EDC and sign off on blah, blah, blah patients,’ without specifying the trial or EDC platform. They assume you’re only handling their trial. With 600 concurrent trials, this is a huge time-waster. I have to sift through emails to figure out what they’re referring to, which adds unnecessary waste to the process.”

Source: ProofPilot* Blog

A look at the startup landscape across clinical development chain supports this view - while dozens of startup companies have emerged in recent years to solve pain points for research stakeholders, the current market is populated with a host of disparate point solutions, occupying adjacent spots on the value chain.

The view I have come to about opportunities in the clinical development technology space is that it is actually less about what you do and way more about how you do it. Meaning, companies need to actually reduce the complexity burden for their customers to generate strong, sticky traction. And this might mean doing a lot of “things that don’t scale.”

For example, while research stakeholders might theoretically be able to generate value from technology on a self-serve basis via great product design, channel checks with customers suggest that they often have a lot of competing priorities, which makes it hard to fully realize value from tech on their own. My sense is that technology companies that embed a robust services layer into their offering to ensure customers actually realize the value from the product will be really well positioned to win share in the market. This is a case where startups may need to trade gross margin for adoption, speed-to-value and retention.

What might successful startups look like at scale?

In the near to medium term, I think there are 9-figure value opportunities to build the “glue” for supply and demand aggregators to reduce complexity via better network integration.

Over the long term, I think there could be a 10-figure or even an 11-figure value opportunity to build some kind of tech-enabled middleware platform connecting the two sides of this marketplace. Maybe this kind of platform even disintermediates the incumbent supply and demand aggregators over time.

Whether these platform opportunities emerge as the result of consolidation of existing startups or from the emergence of a purpose-built, end-to-end platform, or a combination of both, reducing complexity for biopharma research stakeholders is a very promising market opportunity, and one that I am closely watching as an early-stage investor.

Ultimately, science is hard. In the absence of some world-changing discovery catalyst, every marginal scientific breakthrough becomes inherently harder to achieve (the oft-cited “Eroom’s law” of drug discovery). But entrepreneurs who can simplify the multi-variate complexity that plagues research today for pharma companies, research sites and most importantly - patients, will find themselves rewarded while accelerating this critically important engine of innovation and human progress.

* Denotes a Sopris Capital Portfolio Company